|

|

|

||

|

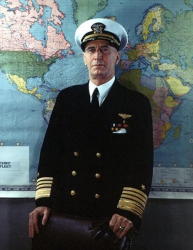

Ernest Joseph King |

||||

|

Graduate, U.S. Naval Academy, Class of 1901 Engagements: • Spanish-American War (1898)• World War I (1914 - 1918)• World War II (1941 - 1945) |

||||

| Biography: | ||||

|

Biography The Early Years Ernest Joseph King was born in Lorain, OH, on 23 November 1878, the son of James Clydesdale and Elizabath King (nee Keam). As a young boy, King read an article in the Youth's Companion about the Naval Academy which stimulated his interest towards a Navy career. Upon graduating from Lorain High School in 1897, he was appointed to the Naval Academy by Representative Kerr of the Fourteenth District of Ohio. When he left home, his father, a railway mechanic, gave him a round-trip railway pass in case he might change his mind. Although he never used the return portion, he did keep it for many years. In the summer of 1898, during the Spanish American War, as a Naval Cadet, King served in the protected cruiser USS San Francisco (C-5), flagship of the Northern Patrol Squadron (her duties consisted of patrols along the Florida coast and off Cuba). King soon found himself under enemy fire off the Cuban coast when his ship engaged enemy shore batteries. For his participation in this action, he received his first award, the Sampson Medal. He graduated with distinction (fourth in his class) in the Class of 1901. During his 1st class year at the Academy, King attained the rank of Cadet Lieutenant Commander, the highest possible cadet ranking at that time. After graduation, he served as the navigation officer on the survey ship USS Eagle (1898); as the engineering officer aboard the battleships USS Illinois (BB-7), USS Alabama (BB-8) and USS New Hampshire (BB-25); and the protected cruiser USS Cincinnati (C-7). On 7 June 1903, after serving two years at sea, King received his commission as an Ensign. [Until 1912, a Midshipman graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy was required to have two years of sea duty as a warrant officer before receiving a commission as an Ensign.] On 7 June 1906, King received simultaneous promotions, first to lieutenant (j.g.) and then to lieutenant. In 1912, King returned to shore duty at the Academy and, while there, he was promoted to lieutenant commander on 1 July 1913. He next selected what were, at the time, cutting edge assignments in America's fast developing Fleet - destroyers and submarines. Gaining the favorable notice of his superiors, King was awarded with his first sea command when he was appointed captain of the destroyer USS Terry (DD-25) in 1914, participating in the United States occupation of Veracruz. He was next given command of a more modern ship, the destroyer USS Cassin (DD-43). Here, King also found himself an aide to Admiral Sims who, while nearly ordering King's court martial for impudence, also recognized King's rare leadership abilities. World War I During WWI he served on the staff of Vice Admiral Henry T. Mayo, the Commander-in-Chief, Atlantic Fleet. As such, he was a frequent visitor to the Royal Navy and occasionally saw action as an observer on board British ships. It appears that his Anglophobia developed during this period, although the reasons are unclear. King was awarded the Navy Cross "for distinguished service in the line of his profession as assistant chief of staff of the Atlantic Fleet." King was promoted to commander on 1 July 1917 and promoted to captain on 21 September 1918. After the war, King, now a captain, became head of the Naval Postgraduate School. Along with Captains Dudley Wright Knox and William S. Pye, King prepared a report on naval training that suggested changes to naval training and career paths. Most of the report's recommendations were accepted and became policy. Submarines Prior to WWI, King served only in the surface fleet. As a junior captain, the best sea command he was able to secure in 1921 was the stores ship USS Bridge (AF-1). However, the relatively-new submarine force offered the prospect of advancement so, from 1923 to 1925, King held several posts associated with submarines. King attended a short training course at the Naval Submarine Base New London before taking command of a submarine division; flying his commodore's pennant from USS S-20. He never earned his Submarine Warfare insignia, although he did propose and design the now-familiar dolphin insignia. In September 1923, he took over command of Submarine Base New London itself. During this period, the raising of the submarine USS S-51 brought King national acclaim for the way he organized the successful salvage of the boat despite the worst sea conditions in more than a decade. His action earned him the first of his three Distinguished Service Medals. Aviation In 1926, Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, asked King if he would consider a transfer to naval aviation. King accepted the offer and took command of the aircraft tender USS Wright (AV-1) with additional duties as Senior Aide on the Staff of Commander Air Squadrons, Atlantic Fleet. That year, the United States Congress passed a law (10 USC Sec. 5942) requiring commanders of all aircraft carriers, seaplane tenders, and aviation shore establishments be qualified naval aviators. As a result, King decided to take advantage of a special abbreviated program that allowed senior officers to earn their wings as naval aviators or observers. King applied for, and was accepted into, postwar pilot training; he reported to Naval Air Station Pensacola for aviator training in January 1927. He was the only captain in his class of twenty, which also included Commander Richmond K. Turner. King received his "wings of gold" as Naval Aviator No. 3368 on 26 May 1927 and resumed command of Wright. For a time, he frequently flew solo, flying down to Annapolis for weekend visits to his family, but his solo flying was cut short by a naval regulation prohibiting solo flights for aviators aged 50 or over. However, the History Chair at the Naval Academy from 1971-1976 disputes this assertion, stating that after King soloed, he never flew alone again. His biographer described his flying ability as "erratic" and quoted the commander of the squadron with which he flew as asking him if he "knew enough to be scared?" Between 1926 and 1936 he flew an average of 150 hours annually. Except for a brief interlude overseeing the salvage of USS S-4, King commanded Wright until 1929. He then became Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics under Rear Admiral William Moffett. The two fell out over certain elements of Bureau policy, and he was replaced by Commander John Henry Towers and transferred to command of Naval Station Norfolk. On 20 June 1930, King became captain of the carrier USS Lexington (CV-2) - then one of the largest aircraft carriers in the world - which he commanded for the next two years. In 1932 he attended the Naval War College. In a war college thesis entitled "The Influence of National Policy on Strategy," King expounded on the theory that America's weakness was Representative Democracy: "Historically... it is traditional and habitual for us to be inadequately prepared. Thus is the combined result of a number factors, the character of which is only indicated: democracy, which tends to make everyone believe that he knows it all; the preponderance (inherent in democracy) of people whose real interest is in their own welfare as individuals; the glorification of our own victories in war and the corresponding ignorance of our defeats (and disgraces) and of their basic causes; the inability of the average individual (the man in the street) to understand the cause and effect not only in foreign but domestic affairs, as well as his lack of interest in such matters. Added to these elements is the manner in which our representative (republican) form of government has developed as to put a premium on mediocrity and to emphasize the defects of the electorate already mentioned." Following the death of Admiral Moffet in the crash of the airship USS Akron (ZRS-4) on 4 April 1933, King became Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, and was promoted to Rear Admiral (UH) on 26 April 1933. As Bureau Chief, King worked closely with the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, Rear Admiral William D. Leahy, to increase the number of naval aviators. At the conclusion of his term as Bureau Chief in 1936, King became Commander, Aircraft, Base Force, at Naval Air Station North Island, San Diego, CA. He was promoted to Vice Admiral on 29 January 1938 on becoming Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force - which, at the time, was one of only three vice admiral billets in the US Navy. King hoped to be appointed as either CNO or Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Fleet, but on 15 June 1939, he was posted to the General Board, an elephant's graveyard where senior officers sat out the time remaining before retirement. A series of extraordinary events would alter this outcome. World War II King's career was resurrected by one of his few friends in the Navy, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Harold "Betty" Stark, who realized that King's talent for command was being wasted on the General Board. Stark appointed King as Commander-in-Chief, Atlantic Fleet in the fall of 1940, and he was promoted to Admiral on 1 February 1941. Anticipating a potential need for landing troops under fire on the beaches of Asia and Europe, King ordered the 1st Marine Division, commanded by Major General Holland Smith, to practice landings in the Caribbean in February 1941. The results revealed how unprepared America was for this task. King then became instrumental in creating an amphibious Navy using landing craft which didn't exist at that time. On 30 December 1941, he became Commander-in-Chief, United States Fleet; on 18 March 1942, he was also appointed Chief of Naval Operations, relieving Admiral Stark. King is the only person to hold this combined command. After turning 64 on 23 November 1944, he wrote a message to President Roosevelt to say he had reached mandatory retirement age. Roosevelt replied with a note reading "So what, old top?" On 17 December 1944 he was promoted to the newly created 5-star rank of Fleet Admiral. In 1945, when the position of Commander-in-Chief, U. S. Fleet ceased to exist, as an office established by the President pursuant to Executive Order 99635, Admiral King became Chief of Naval Operations in October of that year. In December 1945 he was relieved by Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz. From that time he served in an Advisory Capacity in the office of the Secretary of the Navy and as President of the Naval Historical Foundation. He retired on 15 December 1945 but was recalled as an Advisor to the Secretary of the Navy in 1950. Military Medals & Awards In addition to receiving Naval Aviator Wings, King received the following military medals and awards from the U.S. Navy: Navy Cross King was also the recipient of several foreign awards (shown in order of acceptance and if more than one award for a country, placed in order of precedence): Grand Cross of the National Order of the Légion d'honneur (France) 1945 Other Honors The guided missile destroyer USS King (DDG-41) was named in his honor and commissioned on 17 November 1960. A major high school in his hometown of Lorain, OH, bore his name (Admiral King High School) until it was merged with the city's other high school in 2010. The Department of Defense high school on Sasebo Naval Base, in Japan is named after him. Thus, the official name of Ernest J. King School, Navy 3912, FPO San Francisco, CA, became effective School Year 1956/57. King Hall, the dining hall at the U.S. Naval Academy, is named after him. King Hall, the auditorium at the Naval Postgraduate School, is also named after him. Recognizing King's great personal and professional interest in maritime history, the Secretary of the Navy named in his honor an academic chair at the Naval War College to be held with the title of the Ernest J. King Professor of Maritime History. Personal During his years at the Academy, King met Martha Rankin ("Mattie") Egerton, a Baltimore socialite, and they were married in a ceremony at the Naval Academy Chapel on 10 October 1905. They had six daughters, Claire, Elizabeth, Florence, Martha, Eleanor and Mildred; and then a son, Ernest Joseph King, Jr. (Commander, USN retired). After retiring, King lived in Washington, DC. He was active in his early post-retirement, but suffered a debilitating stroke in 1947, and subsequent ill-health ultimately forced him to stay in Naval Hospitals at Bethesda, MD, and at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, ME. He died in Kittery on 25 June 1956. King was buried with the highest military honors in the United States Naval Academy Cemetery at Annapolis, MD. He was survived by his wife, Martha, who died on 6 December 1969. She is buried next to her husband at Annapolis. Analysis of Naval Career of Ernest Joseph King King's Personality King was highly intelligent and extremely capable, but controversial. Some consider him to have been one of the greatest admirals of the 20th century; others, however, point out that he never commanded ships or fleets at sea in war time, and that his Anglophobia led him to make decisions which cost many Allied lives. Others see as indicative of strong leadership, his willingness and ability to counter both British and U.S. Army influence on American World War II strategy, and praise his sometimes outspoken recognition of the strategic importance of the Pacific War. His instrumental role in the decisive Guadalcanal Campaign has earned him admirers in the United States and Australia, and some also consider him an organizational genius. He was considered rude and abrasive and, as a result, King was loathed by many officers with whom he served. He was perhaps the most disliked Allied leader of World War II. Only British Field Marshal Montgomery may have had more enemies. King also loved parties and often drank to excess. Apparently, he reserved his charm for the wives of fellow naval officers. On the job, he "seemed always to be angry or annoyed." There was a tongue-in-cheek remark about King, made by one of his daughters and carried about by naval personnel at the time, that "he is the most even-tempered person in the United States Navy. He is always in a rage." Roosevelt once described King as a man who "shaves every morning with a blow torch". It is commonly reported that when King was called to be Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Fleet on 30 December 1941, he said; "When they get in trouble they send for the sons-of-bitches." However, when he was later asked if he had said this, King replied that he had not - but that he would have if he had thought of it. King's Response to Operation Drumbeat At the start of the U.S. involvement in WWII, blackouts on the U.S. eastern seaboard were not in effect and commercial ships were not travelling under convoy. King's critics attribute the delay in implementing these measures to his Anglophobia. Using convoys and having seaboard blackouts were British proposals, and King was supposedly loath to have his much-beloved U.S. Navy adopt any ideas from the Royal Navy. He also refused, until March 1942, the loan of British convoy escorts when the USN had only a handful of suitable vessels. He was, however, aggressive in driving his destroyer captains to attack U-boats in defense of convoys and in planning counter-measures against German surface raiders, even before the formal declaration of war by Germany. Instead of convoys, King had the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard perform regular anti-submarine patrols, but these patrols followed a regular schedule. U-boat commanders learned the schedule and coordinated their attacks to these schedules. By leaving the lights on in coastal towns, merchant ships were 'back-lit' to the U-Boats. As a result, there were disastrous shipping losses; two million tons were lost in January and February 1942 alone. Urgent pressure was applied from both sides of the Atlantic, but King resisted the use of convoys because he was convinced that the Navy lacked sufficient escort vessels to make them effective. The formation of convoys with inadequate escort would also result in increased port-to-port time, giving the enemy concentrated groups of targets rather than single ships proceeding independently. Furthermore, blackouts were a politically-sensitive issue - coastal cities resisted, citing the loss of tourism revenue. It was not until May 1942 that King marshalled resources - small cutters and private vessels that he had previously scorned - to establish a day-and-night interlocking convoy system running from Newport, Rhode Island, to Key West, Florida. By August 1942, the submarine threat to shipping in U.S. coastal waters had been contained. The U-boats' "second happy time" ended, with the loss of seven U-boats and a dramatic reduction in shipping losses. The same effect occurred when convoys were extended to the Caribbean. Despite the ultimate defeat of the U-boat, some of King's initial decisions in this theatre could be viewed as flawed. In King's defense, noted naval historian Professor Robert W. Love has stated that "Operation Drumbeat (or Paukenschlag) off the Atlantic Coast in early 1942 succeeded largely because the U.S. Navy was already committed to other tasks: transatlantic escort-of-convoy operations, defending troop transports, and maintaining powerful, forward-deployed Atlantic Fleet striking forces to prevent a breakout of heavy German surface forces. Navy leaders, especially Admiral King, were unwilling to risk troop shipping to provide escorts for coastal merchant shipping. Unscheduled, emergency deployments of Army units also created disruptions to navy plans, as did other occasional unexpected tasks. Contrary to the traditional historiography, neither Admiral King's unproven yet widely alleged Anglophobia, an equally undocumented navy reluctance to accept British advice, nor a preference for another strategy caused the delay in the inauguration of costal escort-of-convoy operations. The delay was due to a shortage of escorts, and that resulted from understandably conflicting priorities, a state of affairs that dictated all Allied strategy until 1944." Other King Decisions Other decisions perceived as questionable were King's resistance to employ long-range Liberators on Atlantic maritime patrols (thus allowing the U-boats a safe area in the middle of the Atlantic - the "Atlantic Gap"), the denial of adequate numbers of landing craft to the Allied invasion of Europe, and the reluctance to permit the Royal Navy's Pacific Fleet any role in the Pacific. In all of these instances, circumstances forced a reevaluation or he was overruled. It has also been pointed out that King did not, in his post-war report to the Secretary of the Navy, accurately describe the slowness of the American response to the off-shore U-boat threat in early 1942. It should be noted, however, employment of long-range maritime patrol aircraft in the Atlantic was complicated by inter-service squabbling over command and control (the aircraft belonged to the Army Air Forces and the mission was the Navy's; and Stimson and Arnold initially refused to release the aircraft.) Although King had certainly used the allocation of ships to the European Theatre as leverage to get the necessary resources for his Pacific objectives, he provided (at General Marshall's request) an additional month's production of landing craft to support Operation Overlord. Moreover, the priority for landing craft construction was changed; a factor outside King's realm. The level of sea lift for Overlord turned out to be more than adequate. The employment of British and Empire forces in the Pacific was a political matter. The measure was forced on Churchill by the British Chiefs of Staff, not only to re-establish British presence in the region, but to mitigate any perception in the U.S. that the British were doing nothing to help defeat Japan. King was adamant that naval operations against Japan remain 100% American, and angrily resisted the idea of a British naval presence in the Pacific at the Quadrant Conference in late 1944, citing (among other things) the difficulty of supplying additional naval forces in the theatre (for much the same reason, Hap Arnold resisted the offer of RAF units in the Pacific). In addition, King (along with Marshall) had continually resisted operations that would assist the British agenda in reclaiming or maintaining any part of her pre-war colonial holdings in the Pacific or the Eastern Mediterranean. Roosevelt, however, overruled him and, despite King's reservations, the British Pacific Fleet accounted itself well against Japan in the last months of the war. General Hastings Ismay, Chief of Staff to Winston Churchill, described King as: "He was tough as nails and carried himself as stiffly as a poker. He was blunt and stand-offish, almost to the point of rudeness. At the start, he was intolerant and suspicious of all things British, especially the Royal Navy; but he was almost equally intolerant and suspicious of the American Army. War against Japan was the problem to which he had devoted the study of a lifetime, and he resented the idea of American resources being used for any other purpose than to destroy the Japanese. He mistrusted Churchill's powers of advocacy, and was apprehensive that he would wheedle President Roosevelt into neglecting the war in the Pacific." Despite British perceptions, King was a strong believer in the Germany First strategy. However, his natural aggression did not permit him to leave resources idle in the Atlantic that could be utilized in the Pacific, especially when "it was doubtful when - if ever - the British would consent to a cross-Channel operation". King once complained that the Pacific deserved 30% of Allied resources but was getting only 15%. When, at the Casablanca Conference, he was accused by Field-Marshal Sir Alan Brooke of favoring the Pacific war, the argument became heated. The combative General Joseph Stilwell wrote: "Brooke got nasty, and King got good and sore. King almost climbed over the table at Brooke. God, he was mad. I wished he had socked him." Following Japan's defeat at the Battle of Midway, King advocated (with Roosevelt's tacit consent) the invasion of Guadalcanal. When General Marshall resisted this line of action (as well as who would command the operation), King stated that the Navy (and the Marines) would then carry out the operation by themselves, and instructed Admiral Nimitz to proceed with the preliminary planning. King eventually won the argument, and the invasion went ahead with the backing of the Joint Chiefs. It was ultimately successful, and was the first time the Japanese lost ground during the war. For his attention to the Pacific Theatre he is highly regarded by some Australian war historians. In spite of (or perhaps partly because of) the fact that the two men both had big egos that kept them from getting along, the combined influence of King and General Douglas MacArthur increased the allocation of resources to the Pacific War. It was also important that King supported MacArthur's bold island-hopping strategy. Final Remarks Although he was not well-liked by most of those with which he served, and despite the fact that he is rarely commended today, Ernest J. King was one of America's great wartime leaders. He was an admiral whose personal input unrelentingly, and directly, altered the course of WWII and helped to make America's victory possible. |

||||

| Honoree ID: 9 | Created by: MHOH | |||

Ribbons

Medals

Badges

Honoree Photos

|  |  |

|  |

|